A simple Guide to RAG

Introduction

- The goal of this quick tutorial is to explain the concept of a RAG in about five minutes. It’s meant for beginners—people who’ve never seen a Retrieval-Augmented Generation workflow before.

- You can play with the full example directly in the Google Colab.

- The RAG we build here is super basic and definitely not production-ready. A real production setup requires a good vector store, monitoring, fine-tuning, guardrails, and a lot more. I’ll publish a follow-up article about a more advanced RAG pipeline. I also intentionally avoided frameworks like LangChain or LlamaIndex so you can actually understand what’s happening under the hood.

What is a RAG?

A RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) system retrieves information from your database—usually a vector store—and injects that info into your prompt. The idea is to force the LLM to base its answer on your data instead of relying on its internal knowledge (and possibly hallucinating).

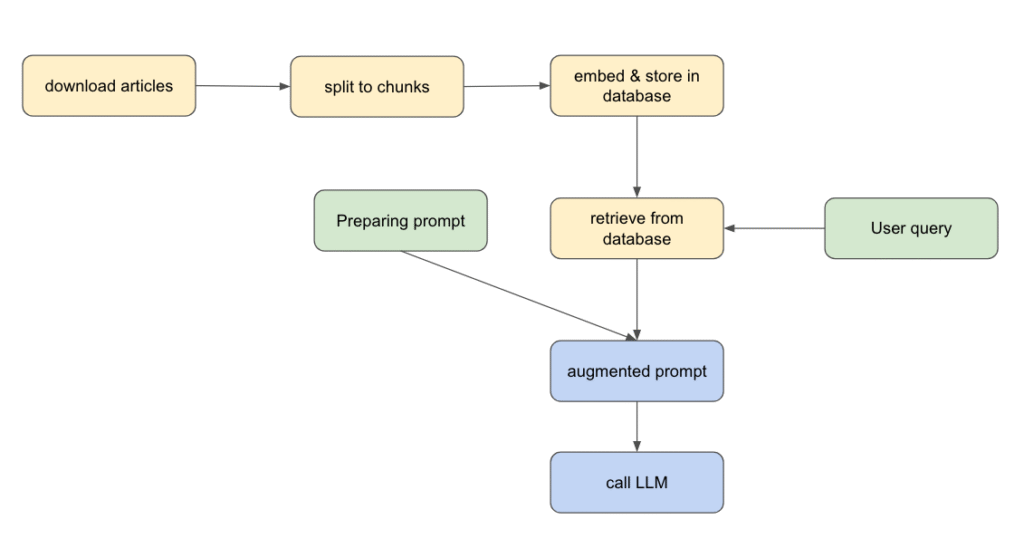

How the RAG pipeline works

1. Download your documents

We grab some scientific articles from ScienceNews using newspaper3k library, a simple and powerful Python library for scraping articles.

from newspaper import Article

urls = [

"https://www.sciencenews.org/article/cholesterol-lowering-pill-enlicitide",

"https://www.sciencenews.org/article/starved-time-poverty-research-autonomy",

"https://www.sciencenews.org/article/glow-light-biophoton-kpop-demon-hunters",

"https://www.sciencenews.org/article/napoleon-army-retreat-russia-bacteria",

]

knowledge_base = []

for url in urls:

article = Article(url)

article.download()

article.parse()

knowledge_base.append({"url": url, "title": article.title, "text": article.text})2. Split each document into chunks

We use LangChain’s RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter to break articles into manageable paragraphs.

splitter = RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter(separators=["\n\n", "\n"], chunk_size=500, chunk_overlap=0)

chunks = []

doc_id = 0

for content in knowledge_base_content:

print(f"Splitting content from {content['url']} ...")

content_chunks = splitter.split_text(content["text"])

for text_chunk in content_chunks:

doc = Document(

page_content=text_chunk,

metadata={"source": content["url"], "title": content["title"]},

id=doc_id

)

doc_id += 1

chunks.append(doc)Let’s see an example of a chunk

Document(id='3', metadata={'source': 'https://www.sciencenews.org/article/cholesterol-lowering-pill-enlicitide', 'title': 'A new cholesterol-lowering pill shows promise in clinical trials'}, page_content='The drug, enlicitide, targets a protein called PCSK9 that binds to and degrades LDL cholesterol receptors in the liver, leaving more LDL cholesterol in the blood. Enlicitide inhibits PCSK9, keeping more LDL receptors in place. That means the liver can ramp up LDL cholesterol removal. Injectable drugs that take this therapeutic approach have become available over the last decade but haven’t been widely used due to cost and other barriers.')

3. Embed each chunk and store them

Each chunk is transformed into a vector embedding that captures its meaning.

For embeddings, we use a free model from Hugging Face. We store everything in ChromaDB as vector store (running in-memory for simplicity). For the moment you can see vector stores as a type of databases in which we store vectors, I will publish lately a post of how this kind of databases work.

Vector stores allow super-fast similarity searches, usually using cosine similarity to measure how close two vectors are.

from langchain_huggingface.embeddings import HuggingFaceEmbeddings

from langchain_chroma import Chroma

embeddings = HuggingFaceEmbeddings(model_name="sentence-transformers/all-mpnet-base-v2")

# in memory vectorstore

vector_store = Chroma(

collection_name="rag_collection",

embedding_function=embeddings,

)

vector_store.add_documents(documents)Let’s try an example, we ask chromadb to retrieve the most similar chunk to our query:

results = vector_store.similarity_search(

"what is a familial hypercholesterolemia",

k=1

)

print(results[0].page_content)>> Due to a faulty cholesterol processing system, people with familial hypercholesterolemia have elevated LDL levels soon after birth, leading to a very high risk of cardiovascular disease. Even with statins and other cholesterol-lowering drugs available, past studies have found that it is difficult for these patients to meet target cholesterol levels, which can vary based on risk factors.

we see that it retrieved a chunk that discusses this issue.

4. Prepare a prompt

Prompt engineering matters—a lot. In this example, we ask the LLM to act like a professional journalist and stick to the context we provide. This is key because we want the model to rely on our database.

We also explicitly tell it not to invent anything to reduce hallucinations.

prompt = """You are an exceptional scientific journalist that answers questions.

You know the following context information

{chunks_formatted}

Answer the following question. Use only information from the previous context information. Do not invent stuff.

- Question: {query}

- Answer: """5. Retrieve relevant chunks

We query the vector store to find the chunks which are the most relevant to the user’s query.

query = "What is the percentage of people who are born with familial hypercholesterolemia"

docs = vector_store.similarity_search(

user_query,

k=3

)6. Augment the prompt

We add those retrieved chunks to the prompt to give the LLM the right context.

docs_formatted = "\n========== \n".join(doc.page_content for doc in docs)

prompt_augmented = prompt.format(chunks_formatted=docs_formatted, query=query)let’s see the content of our prompt

You are an exceptional scientific journalist that answers questions.

You know the following context information

Due to a faulty cholesterol processing system, people with familial hypercholesterolemia have elevated LDL levels soon after birth, leading to a very high risk of cardiovascular disease. Even with statins and other cholesterol-lowering drugs available, past studies have found that it is difficult for these patients to meet target cholesterol levels, which can vary based on risk factors.

==========

The international clinical trial focused on adults who inherited the disorder from one parent. This type affects about 1 in 250 people. The roughly 300 trial participants, ages 18 and up, were already on statin therapy, as per medical guidelines.

==========

Two ongoing clinical trials of enlicitide will assess whether the drug reduces heart attacks and other harmful cardiovascular events and if its cholesterol-lowering effects extend to those without the inherited disorder. Preliminary results for the latter trial, presented November 8 at the American Heart Association meeting, found enlicitide sharply reduced cholesterol levels for people who had previously had — or were at high risk for — a heart attack or stroke, but didn’t have familial hypercholesterolemia.

Answer the following question. Use only information from the previous context information. Do not invent stuff.

- Question: What is the percentage of people who are born with familial hypercholesterolemia

- Answer: We see that the retrieved chunks contains the answer, let’s hope that our llm will use it to give his answer

7. Query the LLM

That’s it: we send the final prompt to the LLM and let it generate the answer.

In this example, we are using openai’s model gpt5-nano. In orde to use, you have to create an account (if you don’t have already one) and generate a token (from here). You need to replace <OPENAI_API_KEY> with your token

import os

from openai import OpenAI

os.environ["OPENAI_API_KEY"] = "<YOUR_OPENAI_API_KEY>"

client = OpenAI()

response = client.responses.create(

model="gpt-5-nano",

input=prompt_augmented

)

print(response.output_text)>> 0.4% (about 1 in 250 people).

We see that the LLM used the information from the context 🙂

8. Conclusion:

I hope this short tutorial has given you a clearer idea of what a RAG is. Don’t forget that running a RAG in production requires additional effort, such as proper evaluation. In the next article, we’ll dive into evaluating the retriever component (getting chunks from the vector store) using LlamaIndex.